Bedbug Profile

Bedbugs belong to the insect order Hemiptera, the true bugs, most of which are winged insects adapted to sucking plant sap. One family of this order, Cimicidae, has evolved as wingless, blood-sucking parasites on warm-blooded hosts.

There are 91 species in this family of ectoparasites (parasites that live on the exterior of the host organisms). Most of these species live in the nests of either birds or bats. But two species have evolved as ectoparasites of humans; the common bedbug, Cimex lectularius, and the tropical bedbug, Cimex hemipterus.

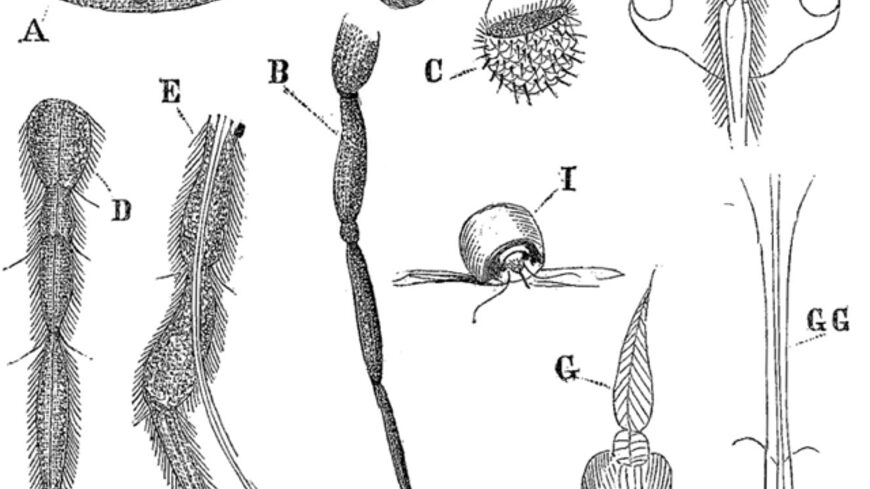

Cimex lectularius is the species most commonly found in homes. Adult bedbugs have oval-shaped bodies with no wings. Prior to feeding, they are about ¼-inch-long and flat as paper. After feeding, they turn dark red and become bloated. Eggs are whitish, pear-shaped and about the size of a pinhead. Clusters of 1-5 eggs can be found in cracks and crevices. Bedbugs prefer to feed on human blood, but will also bite mammals and birds. Bedbugs bite at night, and will bite all over a human body, especially around the face, neck, upper torso, arms and hands.

Bedbugs have a one-year life span during which time a female can lay 200 to 400 eggs depending on food supply and temperature. Eggs hatch in about 10 days. Bedbugs can survive up to six months without feeding. Both male and female bedbugs bite.

History of the Bedbug

The human-host relationship may have evolved when humans still lived in caves and were exposed to cave bats. According to Usinger (1966), the two species of Cimex that feed on humans are related to Old World bat-infesting members of the genus that originated in the Palearctic regions. These species were inadvertently spread by explorers to Africa, Australia and the New World, and became cosmopolitan urban pest species.

In the early 20th century, with the introduction of central heating, the common bedbug spread farther north and became a more serious pest in parts of northern Europe than it had previously been. But with the development of synthetic insecticides such as DDT and spray systems during the Second World War, humans finally gained the upper hand. (Usinger, 1966)

Over the past half-a-century, bedbugs had become a rarity, associated with the most marginal of human living conditions. Unfortunately, to the consternation of urban entomologists and public health officials, bedbugs are once again a major pest issue. A general global resurgence has been reported in Asia, Europe, North America and Australia.

The reasons for this phenomenal resurgence are not yet clearly understood. Many factors may be playing a role. These factors include:

- Changes in registered pesticides, use patterns, residual levels and pesticide resistance.

- Socioeconomic conditions leading to increased levels of homeless people living under conditions in which it is difficult to maintain hygiene.

- A populace that has forgotten how to monitor for and control bedbugs.

- Greater mobility that allows bedbugs to spread more quickly to a wide number of establishments, including hostels, shelters, bus stations, dormitories, prisons, hospitals and hotels, and also from one region/country to another.

The Bed Bug Problem in Toronto

In Toronto, reports of bedbugs by pest control companies and pest control officials started to increase in 2001. Homeless people told street nurses that bedbugs were a priority medical issue in 2002. By 2003, at least a dozen shelters, hostels and other forms of public housing were known to have ongoing problems with bedbugs, despite spraying by pest control companies.

In November 2003, a special emergency meeting was organized by Hostel Services of the Toronto Shelter Housing and Support Division, at which advocates for homeless people, shelter personnel, street nurses, public health officials, a university entomologist and a professional pest control services manager came together to draw up an action plan.

This action plan failed to sufficiently address the rising exponential growth of bedbug populations, and the bedbug problem has now become epidemic throughout the city.

Causes for Concern

The bedbug epidemic is a concern for many reasons. First, the nocturnal blood-sucking habits of the bugs induce anxiety, worry, stress and sleeplessness for those infested. The initial bite, though usually painless, may develop into a welt that remains itchy for weeks. With scratching and subsequent infections, these welts can develop into severe skin conditions. This psychological torment alone justifies public health concern.

When the conditions of shelters are such that homeless people prefer not to use them for fear of bedbugs, and sleep in the streets instead, the societal investment in shelters is undermined.

At the same time, the potential of bedbugs for spreading disease cannot be overlooked. According to Harwood and James (1979), bedbugs fulfill all the conditions of efficient carriers of disease (disease vectors). They can be infected with many disease organisms. Ebeling (1978) reported that the organisms associated with plague, relapsing fever, tularemia and Q fever survive for long periods in bedbugs.

Olson (2000) found that bedbugs may play a minor role in the transmission of hepatitis B virus, but not other viruses such as HIV.

Although they have not yet been implicated in the spread of any human epidemics, the medical community should maintain a high level of vigilance, given the bedbug’s disease-carrying potential, the ever-evolving dynamics of disease organisms, and the potential of bedbugs to serve as vectors of blood-born diseases from person to person. However, for practical purposes, bedbugs are officially considered only as medical nuisance pests, not as carriers of disease. (As per Research Bulletin, December 2003, prepared by the Centre for Urban and Community Studies, University of Toronto)

Finally, bedbugs may be a biological indicator of changing social conditions and might foretell the resurgence of other ectoparasites such as lice and fleas and their associated diseases.

The resurgence in 2003 of bedbugs in shelters and other public facilities was not contained and has resulted in a continuous and escalating growth in the source populations, leading to larger-scale infestations, which has required more frequent and costly control efforts.

As the source populations have grown, the rate of spread has inevitably increased and bedbugs now appear in hotels, apartments, theatres, restaurants, public transit, hospitals and in detached single family homes. The bedbug epidemic shows no sign of abatement.

We want to stress that Toronto is not alone or unique in experiencing a bedbug resurgence. There is an epidemic of bedbugs across North America, Australia and Europe, not only in shelters, public housing, hostels, hospitals, prisons and other institutions, but also in five-star hotels and other upscale urban hospitality establishments.